“Stamps and Maps” – Ali Acerol

Ali Acerol “Stamps and Maps” at Sharq Gallery

March 5 – 12, 2017

Reviewed by Karen Woodward Sarrow

I recently attended the reception for Sharq Gallery’s posthumous show for Ali Acerol. The Sharq Gallery was built by Nahid Massoud and Robert Rosenstone after 9-11, with a mission is to show the work of bicultural artists with roots in the East. Sharq means “the East” in Farsi, while in Arabic the term is “Al Sharq.” The gallery is located in a residential neighborhood that overlooks the Pacific ocean, in the midst of a sustainable succulent garden, meticulously maintained by Massoud. This gallery is a light-filled, peaceful respite devoted to building bridges between cultures. Sharq has provided artists, writers, and musicians an inspirational performance venue since 2004. These artists have originated from Iraq, Israel, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Armenia, Mauritania, Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Lebanon, Turkey, as well as the United States and Canada.

In March, Robert Rosenstone introduced Richard Hertz, author of the memoir and poetry book of Ali Acerol, “Three-Story Man in a One-Story Town.” Hertz spoke about Acerol’s work and life to a multigenerational audience, including Acerol’s time at Cal Arts, and his popularity in Santa Monica. The well-curated show was standing-room only that afternoon, including Acerol’s daughters and grandchildren.

Acerol was born in Bursa, Turkey in 1948. He experienced an idyllic childhood in Turkey, at a time when modern conveniences, like trash collecting, were being introduced. As a young man, he set out to explore his homeland, bravely hitchhiking from town to town and meeting many supportive men along the journey.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Acerol enjoyed an intellectual, bohemian student-life in Paris. He experienced artistic recognition by the curator Darthea Spayer, and fell in love with his future American wife, Klobie, who was studying painting. In his memoir, Acerol often remarks on the extraordinary generosity and shared resources of French immigrants, Parisians, and himself, while he was in Paris.

Klobie and Ali Acerol moved to California, married and had two children. In the late 1970s, Acerol and Klobie began hosting a salon in an industrial live/work space on Euclid Avenue in Santa Monica. It became a legendary hangout for the Los Angeles art world.

Klobie’s family had supported Acerol through Cal Arts, but later, Acerol became estranged from his suburban family. He found supportive friends and generous patrons in Santa Monica, until tragically, alcoholism took his life in 2007

Many of Ali’s paintings and drawings consist of marks that represent sign language. There are thousands of small hands illustrated throughout his maps. His mural-sized drawing of the world map, displayed at Sharq Gallery for the first time since he attended Cal Arts, was his MFA thesis. It emits a humanistic sentiment, and an obsessive devotion to visual communication.

Acerol’s repetition of hands, repeated over different mediums and time spans, with stylistic changes over time, is evidence of Acerol’s wish to connect all people, in the countries important to him, and his friends. It was a profound vision to behold in 2017, when American leadership is displaying unprecedented division against immigrants, Muslims and people of color. Acerol loved all people, and people loved him. His journals confirm his love of humanity with his observations of artists and people he admired. He would go to museums to look at the art—and to watch people. He was drawn to revolutionaries, philosophers, and poets. He would spend hours and days in conversation with his colleagues and friends.

Acerol enjoyed and emulated conceptual art. He admired John Baldesarri’s word play, and the art critic Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe views Acerol as a poet, “both are engaged in making connections that have a logic that can, on a second look, be found in the images out of which the work is made.” In this way, Acerol showed a self-conscious use of both material and content. Acerol used ink and paint to create maps at a time when there was an explosive development of digital imagery and printing occurring. He asserted traditional drawing techniques to create visual manifestations of silent, human communication (sign language), and human exploration and exploitation. He often revealed the grids in his work, a nod to the image transfer process.

Acerol’s commitment to the physicality of art exists in his massive brick and mortar sculptures. He had memories of walking with his father next to community-built fences of Bosporus bricks, corroding from

the salt air along the seaside. He recorded memories of bricks in his domestic space growing up; obsessively carving through a brick wall night after night, to make a path for a toy train.

In his late work, Acerol adopted a simple rendering of the hand, with just a few strokes. It can be tempting to attribute this stylistic change to alcoholism, but it also becomes the distinctive, open hand of the artist’s later work, shown here in a detail of his 2006 painting, “Afghanistan.”

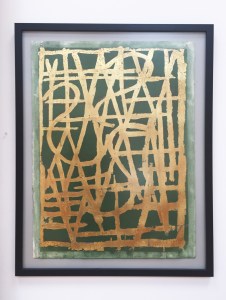

These open marks also have affinities with his overlapping, free hand letter paintings from 2006 to 2007. Curator Nahid Massoud explained that green and gold are the most popular colors of Islamic pottery. Acerol’s memoir also mentions an autobiographical “repeated name” work where he used the same colors that appeared in an Arabic illustration from 600 A.D.

Acerol stated that his father giving him stamp books as a young boy heavily influenced his paintings of stamps. These tightly rendered paintings speak to the experiences of an immigrant, as well as memories and symbols of Turkey.

Ali had a charismatic personality, and it served him well as an artist and poet, though transitioning from a bohemian life to a suburban domesticity was a challenge for him. In contrast to Acerol’s maps and stamps that speak to exploration and human connectivity over long distances, the brick work literally belongs inside the home. He created domestic furnishings from bricks and mortar—sculpting chairs, and a couch (not shown), as well as charming flower vases. Referencing their formal qualities, Acerol called these massive works “third world modernism,” and referenced childhood memories, but their extraordinary weight brings to mind the burdens and trials of domestic life on the creative spirit, and a feeling of permanence.

Ali Acerol’s work represents humanistic, international connectivity, and he epitomizes the strongly independent artist. He addressed this dichotomy in his own inspiring words,

“Human beings can hold opposing ideas in both hands. That is how tolerance starts. Once tolerance begins, it never stops.”

To Contact Sharq: Ph: (310) 459-6041 Email: sharqart@gmail.com